#3 – Ideology

Weekly Review #3 – Notes on Ideology, The Week In Books: Liverpool, W. E. B. Du Bois, Enoch Powell, Umberto Eco's anti-library

The War of All Against All

The history of the world is the history of the warfare between ideologies. What liberals called ‘the market of ideas’ is more a makeshift boxing ring or a battlefield. A perpetual civil war rages between ideologues, with each striving to wield power in pursuit of their interests.

The suggestion that ideas exist in a market was an idea of capitalist, that is to say liberal ideology. In depicting ideologues as an assortment of shopkeepers peacefully peddling their wares, liberalism lassoed and corralled them, absorbing and transforming them all into stalls within its own courtyard.

Nietzsche said life is “the will to power, and nothing besides.” He saw this rooted in natural impulses. A jumble of unconscious appetites and instincts spawn a network of needs and wants. We sculpt the world in the image of our desires, mould it according to our interests, and process it so that our own powers and abilities may thrive.

Foucault and his minions seized on this thought. Power is a diffuse network of force woven into the very fabric of social life, they reasoned. Ideological power-interests are everywhere present at once. They creep forth in all interactions, and leave imprints in any trivial dispute. Even the merest gesture, the simplest question is an act of power.

The war of all against all is a battle for truth: the desire to see one’s own truth, one’s own ideology and power-interests, receive the highest social sanction.

‘Each society has its regime of truth, its ‘general politics’ of truth: that is, the types of discourse which it accepts and makes function as true; the mechanisms and instances which enable one to distinguish true and false statements, the means by which each is sanctioned; the techniques and procedures accorded value in the acquisition of truth; the status of those who are charged with saying what counts as true.’ – Foucault (1972)

Regimes of Truth

In spite of its eternal strife and skirmish, a society is bound together by ideologies. They produce patterns of behaviour, modes of exchange, and they supply the shared symbols and meaning structures that make social life feasible. Certain ways of acting and feeling are accepted and others are spurned.

In The Managerial Revolution, James Burnham notes that ideologies perform a key function: they act as ‘the social cement’, the glue, the adhesive that seals people into cohesive systems. An ideology colours the shades of daily life, and one often begins to think in its terms with almost automatic reflex.

Some kid themselves that they are free from ideology. This is nonsense, for the simple fact that in order to partake in society at even a basic level, one must subscribe to at least the essential tenets of the ideologies that dominate it; one is always an ideologue to some degree. Even the act of being ‘anti-ideological’ is an ideology in itself.

In some societies, there is a single overarching ideology that wields, or seeks to wield, complete and total control over the peoples and institutions within it; we call this a totalitarian ideology.

Some ideologies are rigid, carefully contrived systems of thought with specific convictions and a strong desire to enforce adherence. Most are a mere cluster of standpoints, positions and precepts animated by certain interests. They react to the structures and social relations they are immersed in, and so evolve and mutate over time.

In the Western states, there are several core ideologies at play. Some of these ideologies are in direct competition with each other, although they may have splintered off from the same root and so share specific stances or resemble each other in select traits.

At any one time, there are numerous sub-ideologies that are either new formulations or distorted, twisted versions of the ideologies from which they sprang. Over time, these sub-ideologies can evolve and grow in influence.

They either hitch a ride on the backs of more dominant ideologies, or they gradually amass power through conversion and expansion, thereby becoming one of the central organising ideologies in society.

Ideology Vs. Science

Burnham draws a sharp distinction between ideology and science. Ideology is not scientific, although some ideologies incorporate scientific facts and many like to describe themselves as ‘scientific.’ An ideology is interested in facts only so long as those facts are aligned with its interests. An ideology will discard facts when it is convenient or necessary for it to do so.

An ideology is a collection of ideas, axioms, formulas, values, rules and assertions that express the interests of a group. These interests are activated by emotions such as anger, desire, fear, and hope.

A scientific theory hinges on its ability to interpret and explain data and evidence, which it then uses to predict the future. The strength of a scientific theory is determined by how accurate its predictions are.

An ideology may make use of data and evidence, but will filter them through its hopes and fears for the future, offering a picture of how things should or should not be.

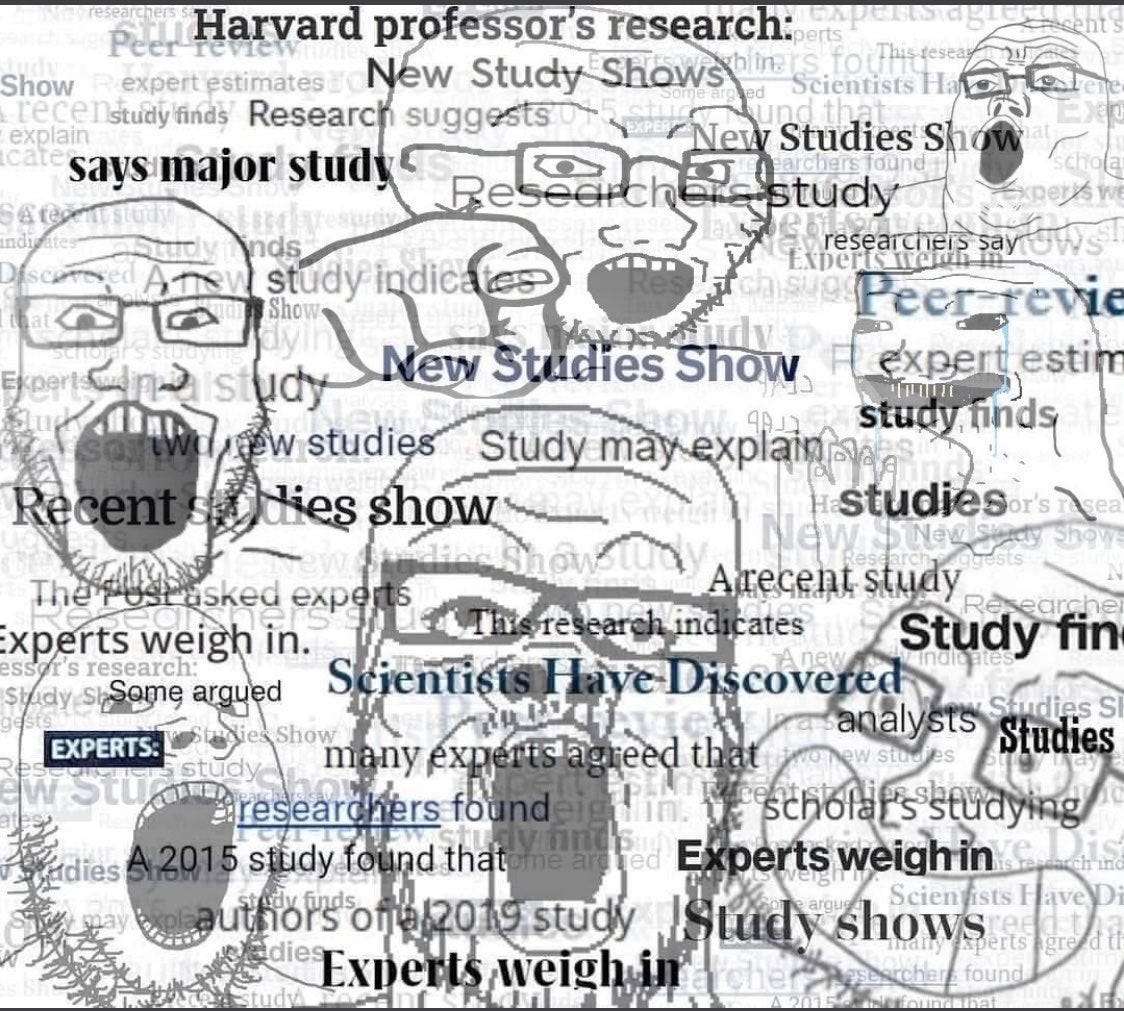

A scientific theory is not normative and does not pass judgement or make propositions as to how things should be – it seeks only to determine and describe how things are. Anything calling itself ‘science’ that deals with the should is not science but ideology. Science is controlled by facts, ideology by emotions.

Science is frequently hijacked by ideologues seeking to lend their ideas a veneer of prestige. Ideologues treat science the same way Nietzsche said bad readers treat books. They “behave like plundering troops: they take away a few things they can use, dirty and confound the remainder, and revile the whole.”

Inventing the Individual

An ideology usually has a core component, an organising principle, an Archimedean point about which its entire system revolves. This is often implicit in its name, but not always. Capitalism and its attendant doctrines are organised around capital, money, production, pursuit of profit.

The two principal schools of capitalism, Liberalism and Conservatism, respectively lay emphasis on ‘liberty’ and ‘conservation.’ Liberalism seeks the freeing up, the unshackling of money as well as of peoples in the pursuit of ‘progress’ or growth. Conservatism seeks to mitigate the effects of unbridled liberty, reduce its wasteful excess, and preserve and protect whatever remains of an old order, even if that old order is merely an earlier version of Liberalism.

Liberalism is the ruling ideology of the West. If any ideology could lay claim to being the dominant ‘regime of truth’, then it would be liberalism. This has been the case since at least the Dual Revolutions of the late 18th century in England and France. The Industrial Revolution eradicated the final remnants of the old feudal order, and the French Revolution gave form to the ideas that would henceforth typify the West.

Liberalism has three core characteristics inherited from Christianity. In some ways each of these have become splinter ideologies in their own right. They are: Individualism, Egalitarianism, and Progressivism, or in simpler terms – the individual, equality, and progress.

In a future post I shall look at how each of these evolved out of Christianity and found a secular footing, and how they are now the levers of pretty much all ideologies in our own day.

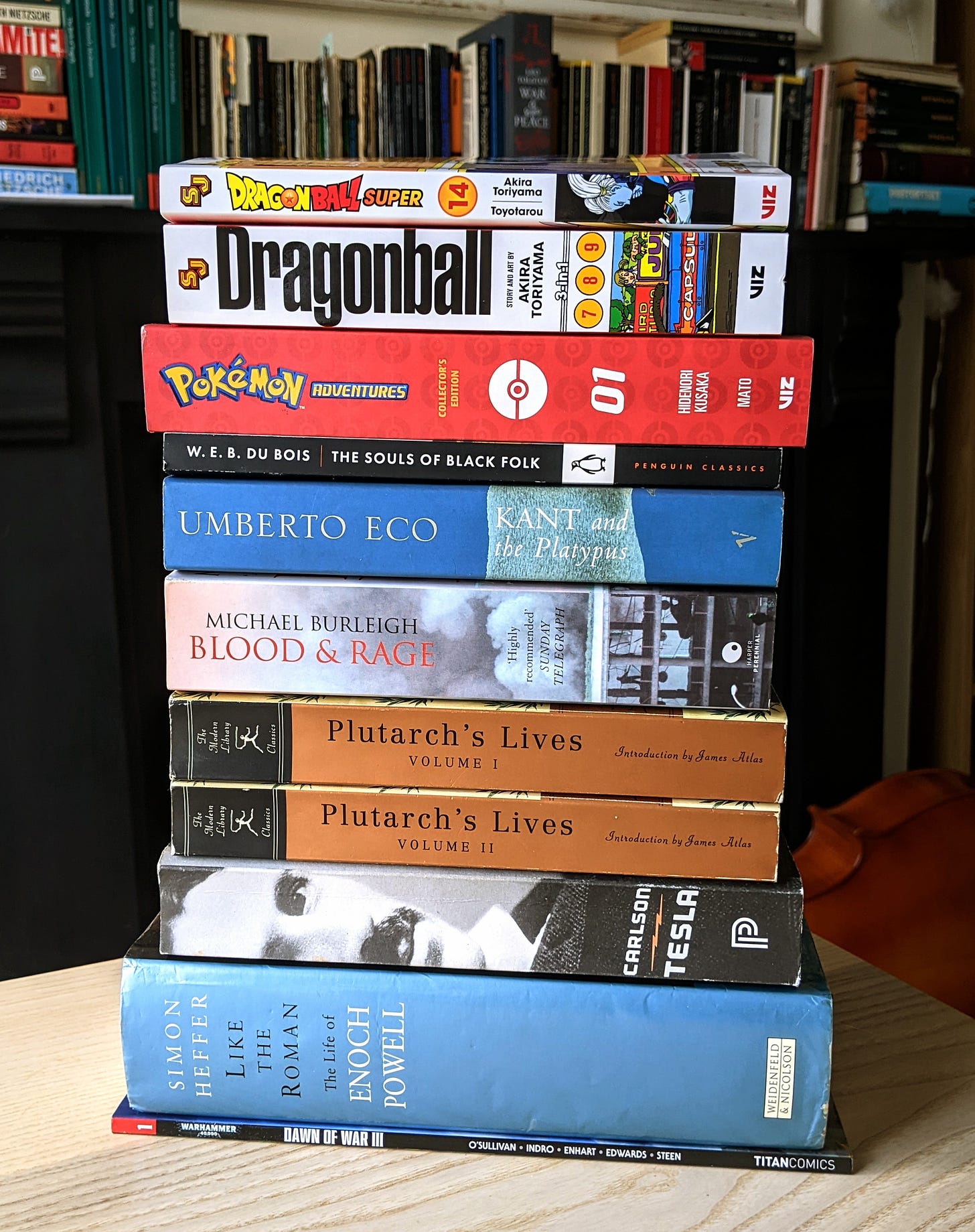

The Week In Books

This week I visited Liverpool. It is one of my favourite cities for book-hunting.

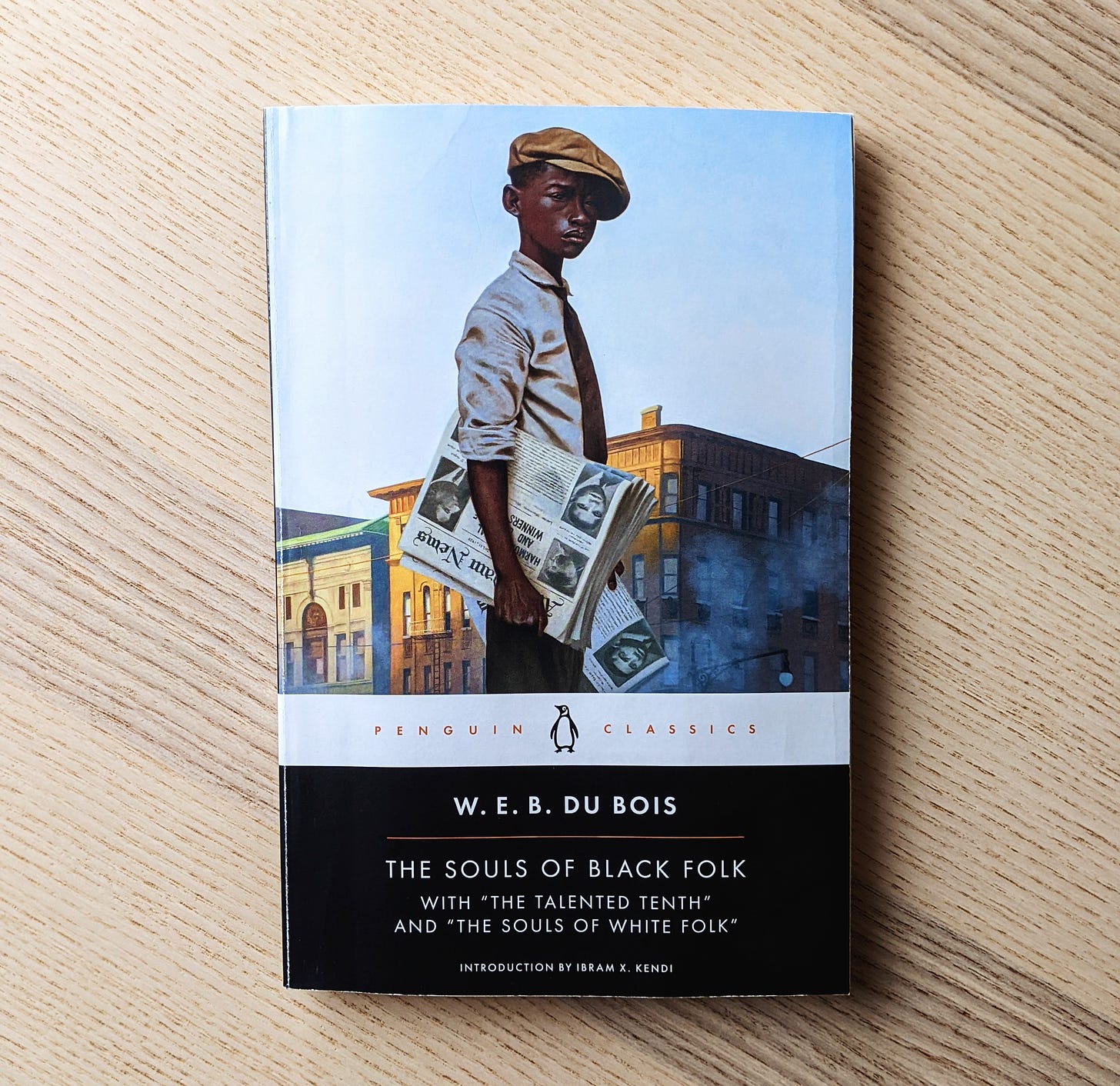

I bought W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk.

I have read a bit about Du Bois but never read his works. He is seen, in some sense, as a precursor to Wokeism, especially in its racial form. He declared in 1903 that the great problem of the Twentieth Century would be the problem of ‘the colour line’ – predicting that the issue of race would hold cardinal significance. He spoke of a ‘double-consciousness’ – the idea that black people in America are beset by ‘two warring ideals in one dark body’, where they are always looking at themselves and judging their qualities through a white Western framework. He proposed the concept of The Veil, which is a mental shroud that maintains this double-consciousness and must be stepped through in order to merge the double self ‘into a better and truer self.’ I have only read the first couple of chapters so far. In terms of the writing style itself, it is succinct, forceful, and replete with lyricism – not at all like that dry fusion of legalese and postmodernist jargon which pretty much typifies most Critical Race Theory pieces of the last 30 years.

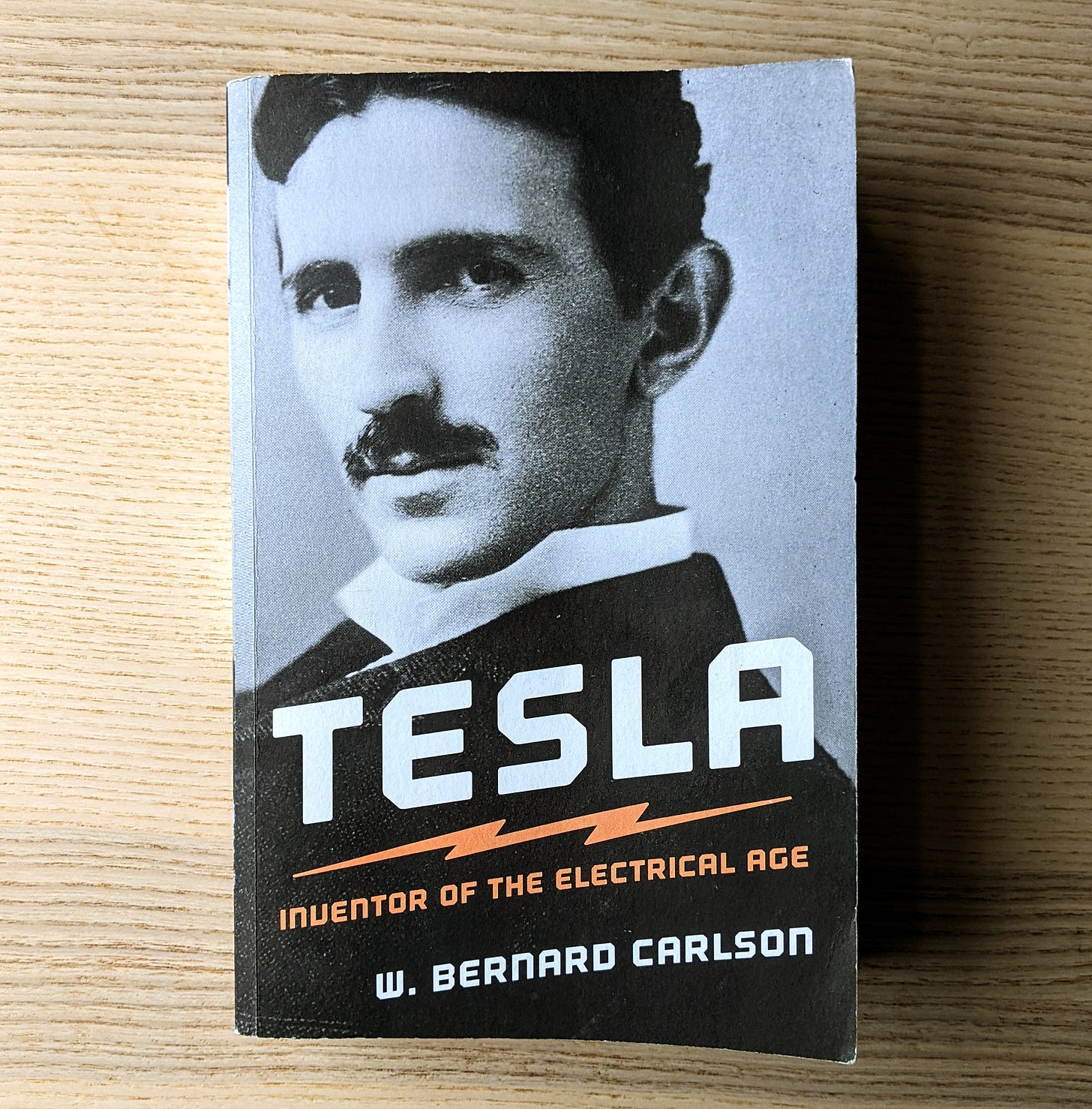

I found an ultra cheap second hand copy of Carlson’s biography of Nikola Tesla.

I first learnt about Nikola Tesla back in Moscow, in the summer of 2008, from my Serbian friends who were obsessed with him, citing him as their national hero. I later saw The Prestige, in which David Bowie played a fictionalised version. And obviously, the name of Tesla has since become synonymous with Elon Musk’s electric vehicle company.

I also got this history of terrorism.

It begins in the 1880s with the Fenian dynamiters of Ireland, before moving onto Russian Nihilist terrorists like Sergei Nechayev (whom Dostoyevsky based one of the main characters in Demons on). It covers the flurry of political killings that followed, the assassinations of Kings and Presidents across the West committed in the name of anarchy. From hereon it deals with international terrorism in the Middle East, to decolonisation, to the Baader-Meinhof Gang in West Germany, a terror outfit that rose from the student protests of the late 60s. Finally it tackles the rise of Islamic terrorism, Salafi-Jihadism, which has profoundly shaped the course of international politics in the last 30 years.

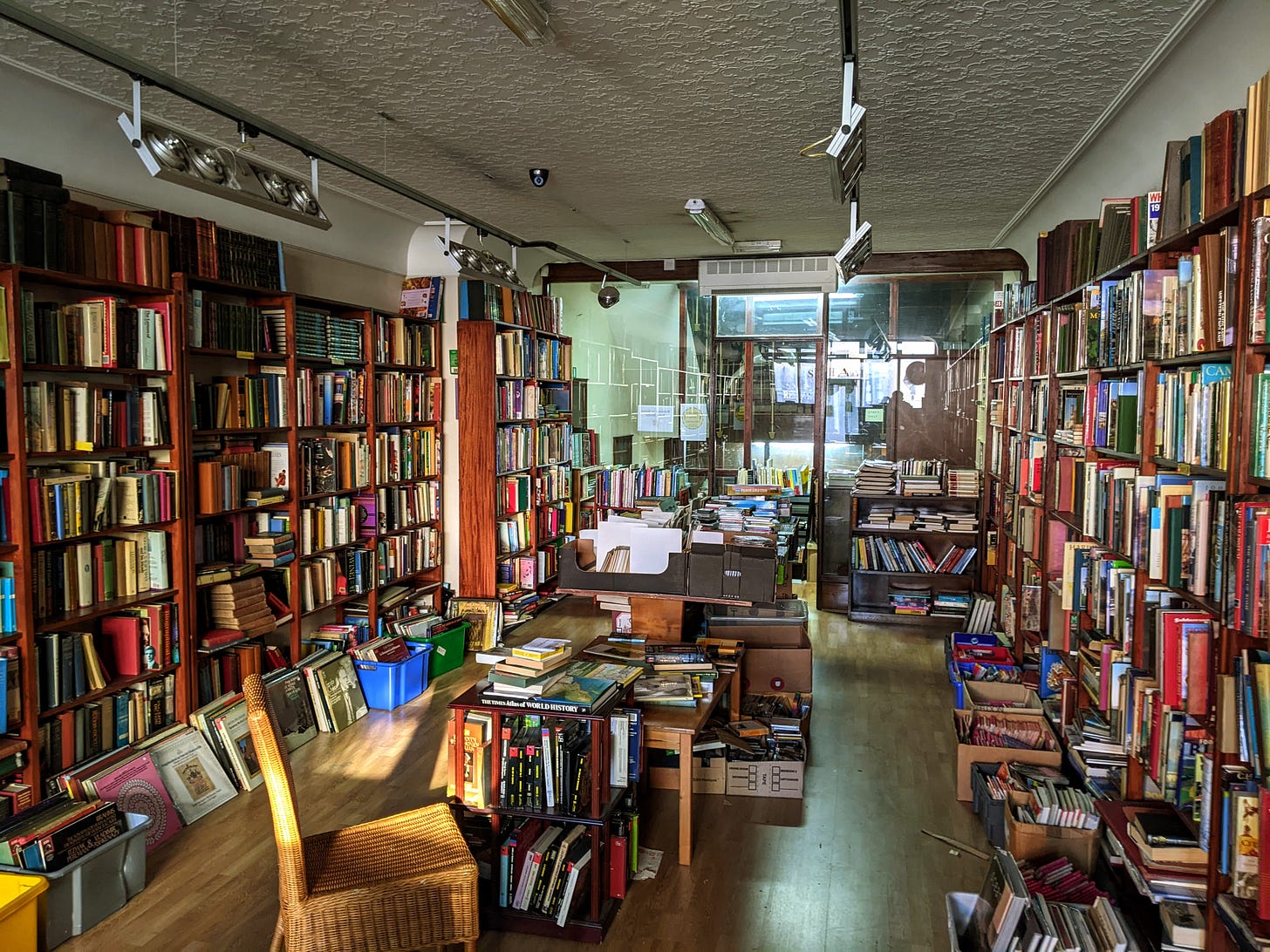

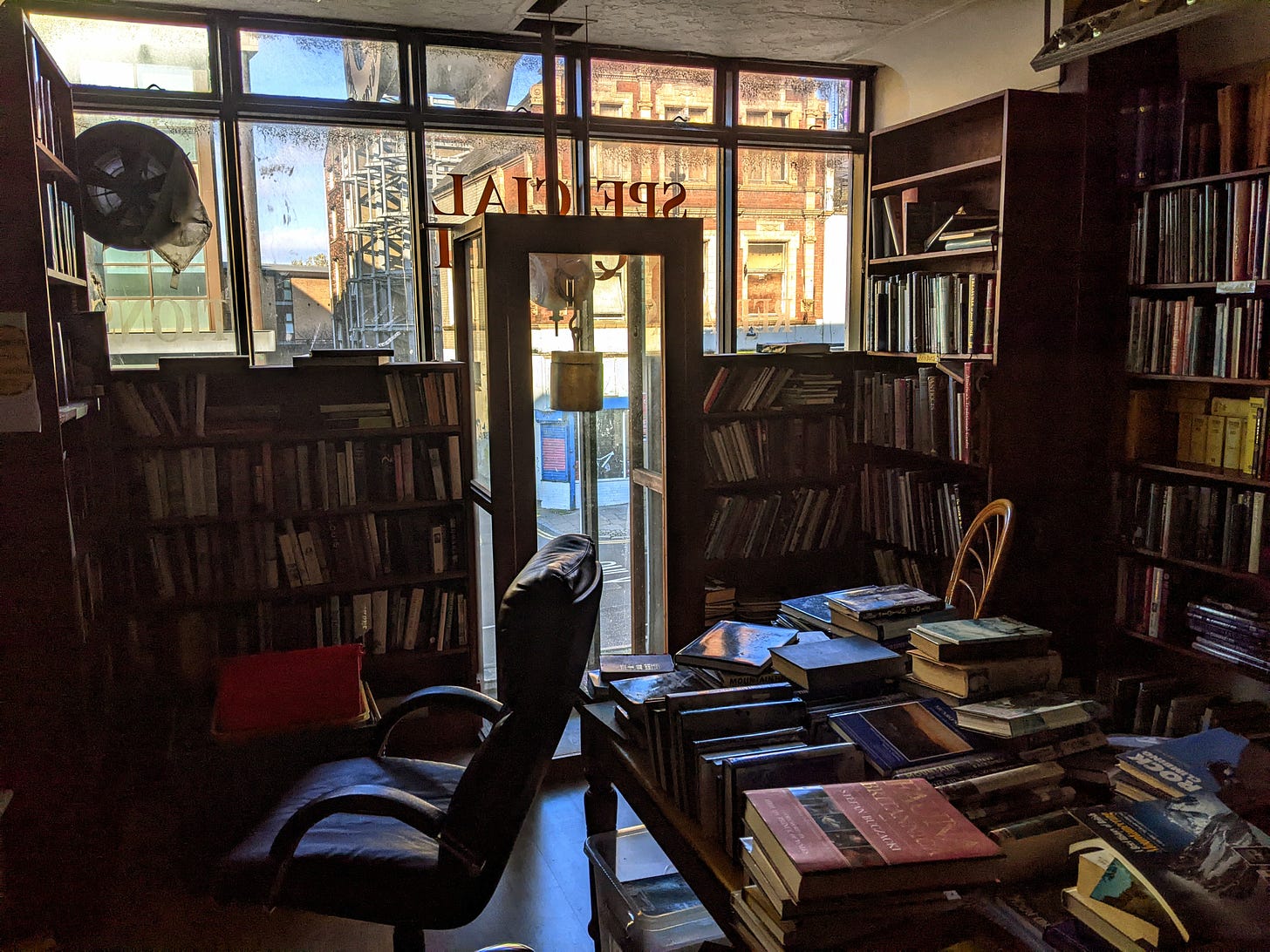

I visited what is probably my favourite bookshop in Liverpool.

It is about a 3 minute walk from Lime Street station and has a huge clock jutting out above its storefront.

It is rammed to the rafters. I have dug up some vital stuff here in the past. I bought Joseph Frank’s 5-volume biography of Dostoyevsky last year, and I’ve unearthed rare items like Machiavelli’s History of Florence here also, amongst much else.

The guy who runs it apparently founded it whilst he was on the dole a couple or more decades ago.

The premises used to be some sort of old medical centre. It has what looks like a huge model of a plastic vulva on the ceiling.

There is an upstairs section with more. Prices here are generally quite cheap.

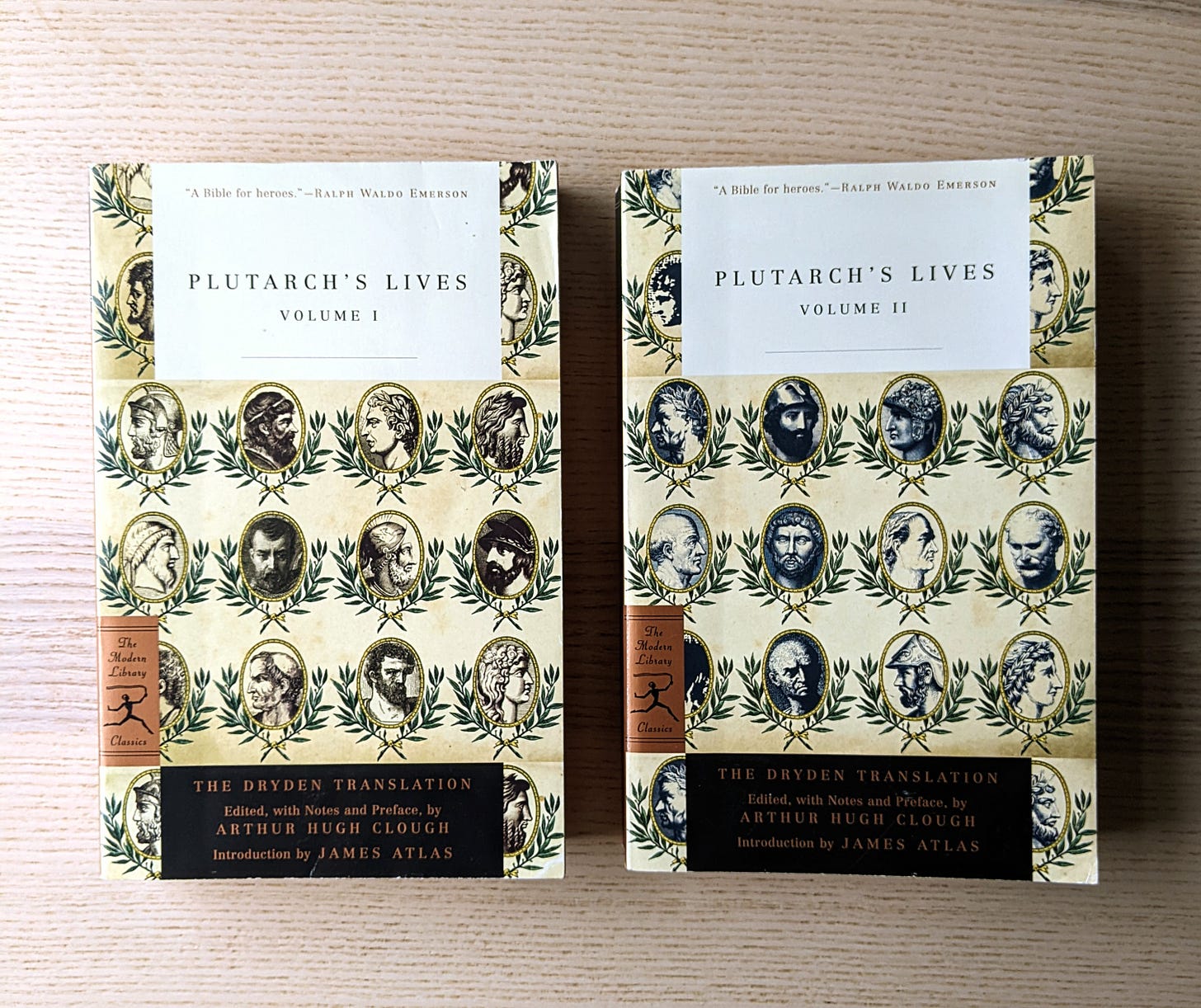

This time I got the complete set of Plutarch’s Lives. I already had some Penguin editions, but these collect them all.

I got Simon Heffer’s biography of Enoch Powell.

Powell is today infamous for his ‘Birmingham Speech’ on immigration, which the press called ‘Rivers of Blood.’ But he is a complex and interesting character. He studied at Cambridge, became a classical scholar, fluent in Latin and various forms of Ancient Greek. He attempted to beat Nietzsche’s record of becoming a professor by the age of 24, but narrowly missed out by a few months. When the second world war broke out, Powell was posted to Cairo and worked in the intelligence unit gathering information on Erwin Rommel’s movements in North Africa. He became the youngest brigadier in the British Army, and after the war ran for political office, becoming a Tory MP. He sought to become viceroy of India but the Suez Crisis in 1956 inaugurated the slow collapse of British Empire, and Powell afterwards became an anti-imperialist.

He worked his way up the greasy Tory pole, becoming Minister of Health in the early 60s. Despite arguing for monetarist economic policies (even before Milton Friedman) and laying the ideological groundwork for Thatcherism, Powell was a staunch nationalist who held that the public welfare was more important than markets. He oversaw the NHS’s Hospital Building Program in the 60s, which led to the construction of most of Britain’s General Hospitals.

In ‘68, 2 weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King and the riots that were raging in its wake in America, Powell delivered the speech that secured his fame/infamy. Using direct quotes from his constituents, and giving air to their grievances, he warned that Britain was ‘busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre’ by allowing immigration to rise at unchecked rates. The speech had him ousted from the Tory shadow cabinet, and he spent the remainder of his political career on the backbenches, or later representing the Ulster Unionists in Northern Ireland.

In the early 70s, he opposed Britain’s entry into the European Economic Community, the ‘common market’. Alongside the Labour MP Tony Benn he became one of the most high-profile figures campaigning against Britain’s continued participation. His argument, like Benn’s, was that the historic doctrine of Parliamentary Supremacy, which held Parliament to be the sole democratic law-making body for the territory of Great Britain, had now been rendered obsolete. In 1992, the EEC became the EU. He delivered predictions about Britain’s eventual and ‘inevitable’ withdrawal from the project. He died in 1998.

Fast forward to 2016 and the two issues which had made Powell the most talked-about politician of his day – immigration and the common market – congealed to create Brexit. To understand Brexit, its motivations, its reasons, its ‘spirit’ of populist backlash – Powell is perhaps the key figure of British political life to be studied.

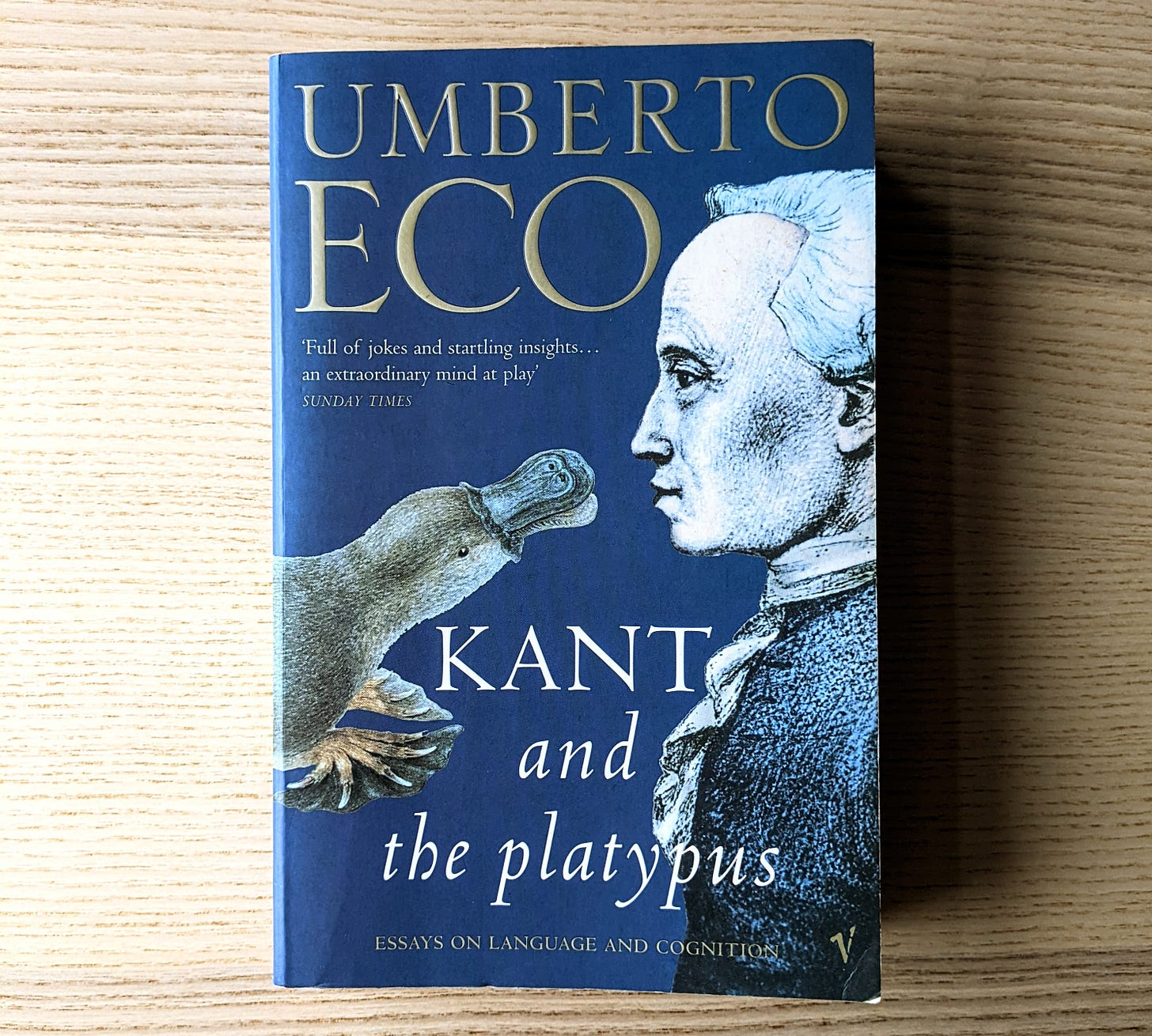

I also got a collection of essays by Umberto Eco. Eco is known primarily for his novels, but he was mainly a semiotics professor at the University of Bologna.

Eco had one of the largest private libraries in Italy. Following his death in 2016, the Italian culture ministry inherited it. This old video of him traversing its many aisles went viral on Twitter again last year.

In The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb says this:

The writer Umberto Eco belongs to that small class of scholars who are encyclopedic, insightful, and nondull. He is the owner of a large personal library (containing thirty thousand books), and separates visitors into two categories: those who react with “Wow! Signore professore dottore Eco, what a library you have. How many of these books have you read?” and the others—a very small minority—who get the point that a private library is not an ego-boosting appendage but a research tool. The library should contain as much of what you do not know as your financial means, mortgage rates, and the currently tight real-estate market will allow you to put there. You will accumulate more knowledge and more books as you grow older, and the growing number of unread books on the shelves will look at you menacingly. Indeed, the more you know, the larger the rows of unread books. Let us call this collection of unread books an antilibrary.

I took this passage somewhat to heart, or at least used it as a justification for what is most probably some sort of obsessive compulsive addiction.

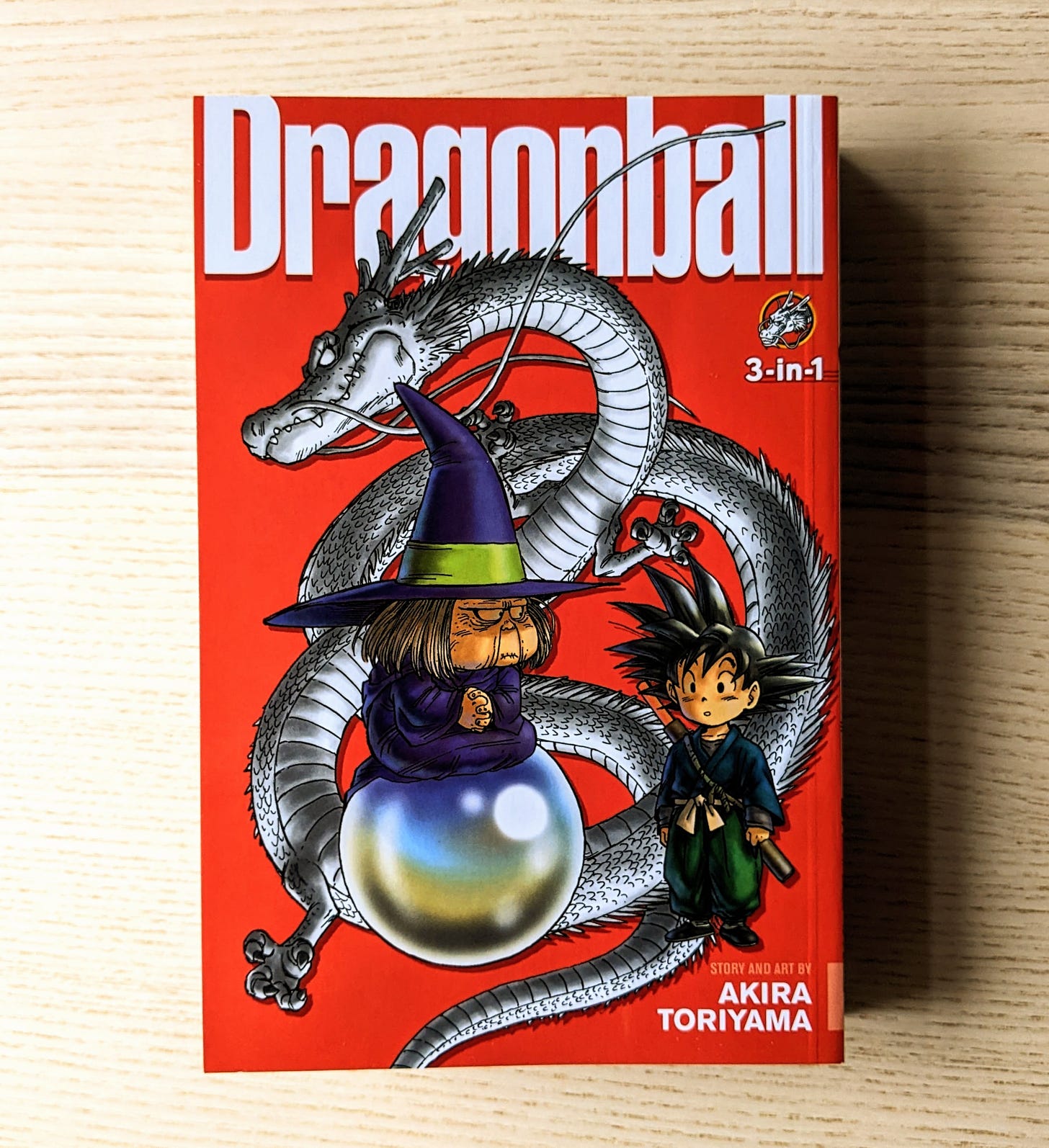

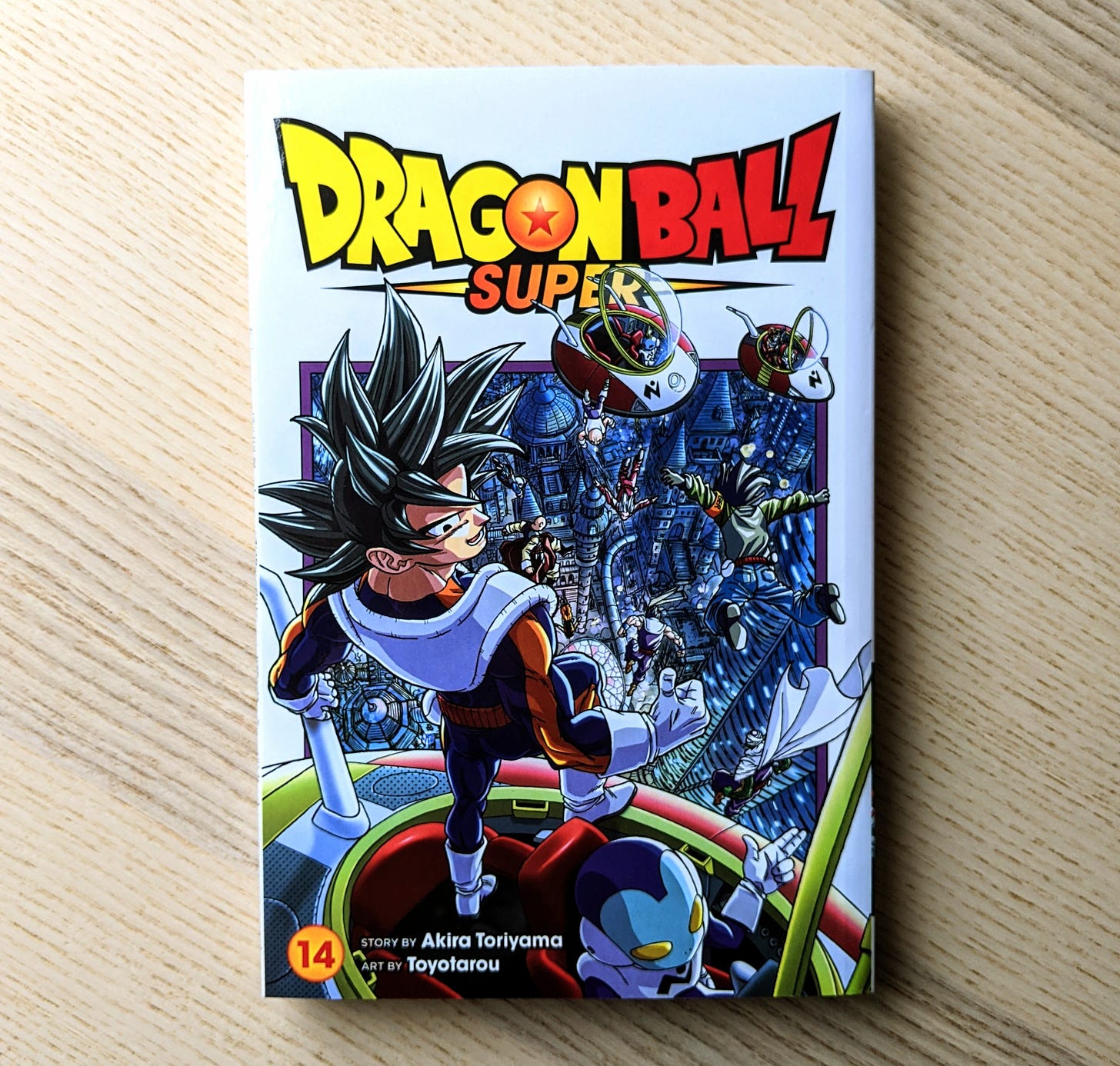

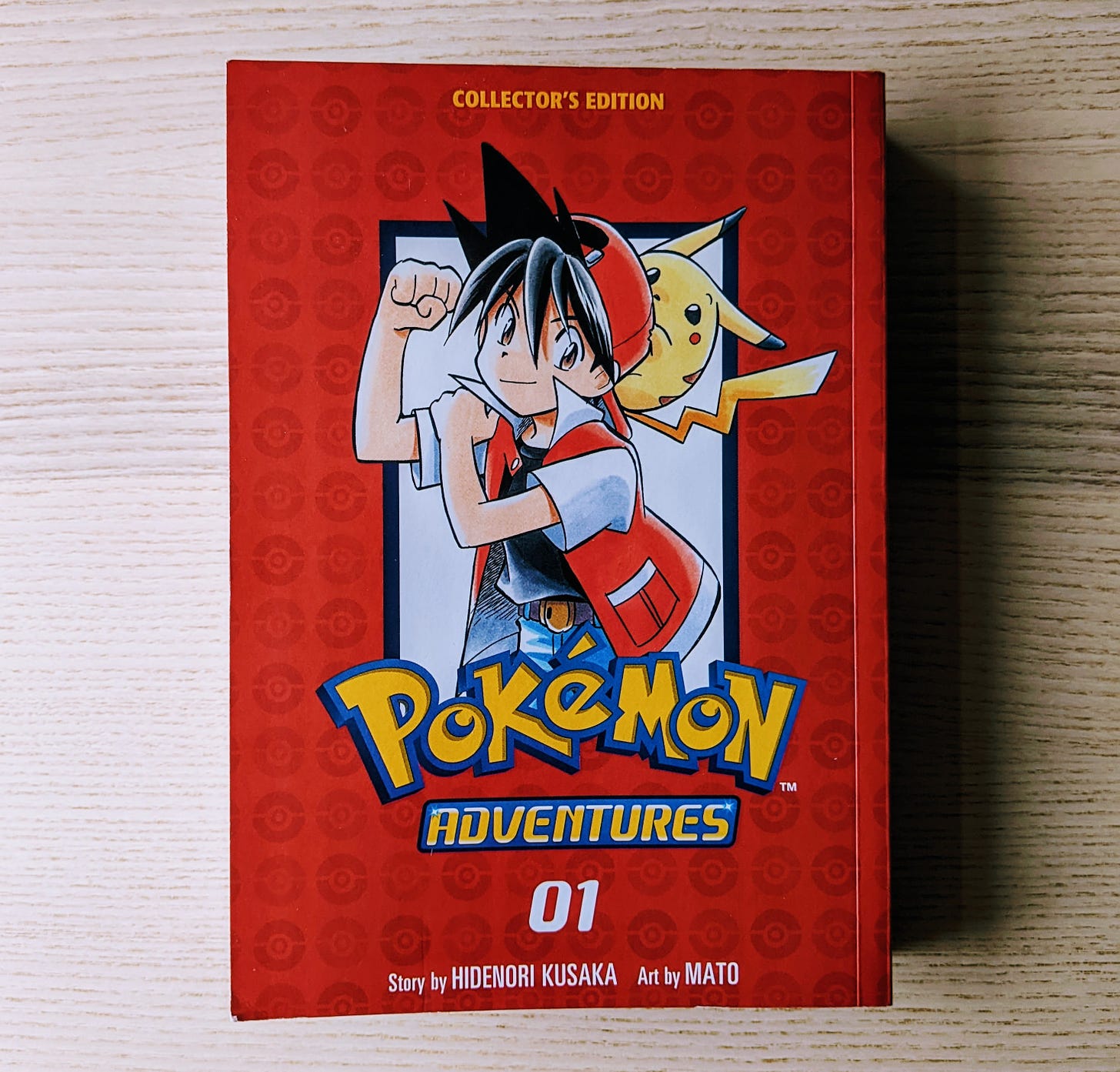

Finally, on a somewhat lighter and more ‘childish’ note, I bought some manga from a shop called Worlds Apart.

As a kid I was obsessed with Dragonball Z. I never watched nor read the original Dragonball series that preceded it. A few months back I ended up finally buying the first volume. I now think it’s actually better than the Z series, certainly much funnier.

I have also been reading the newer Dragonball Super series here and there for the past few months.

I bought this Pokemon volume for its nostalgia. I had the first part as a child, along with another series of comics called ‘The Electric Tale of Pikachu.’ Sometimes it’s good to revisit things that brought you enjoyment as a kid.